Martha’s Vineyard Case Study

Map

To Navigate

To explore this map, hover over a point to see the location’s name. The purple polygons represent the Aquinnah-Wampanoag Trust Lands that are federally recognized. The points are color coded by whether the place is officially recognized by the United States Government. The map intentionally does not include the state boundaries demarcated by the United States government.

Discussion

The island of Martha’s Vineyard stands as a good case study because its boundaries are self-contained and it is a place with both predominantly white spaces with Indigenous place names and the use of an Indigenous place name by and for an Indigenous space. There are a variety of places on the island that fit the criteria of being predominantly white spaces using Indigenous place names, but for the purpose of this case study I will be comparing Chappaquiddick Island with Aquinnah. Aquinnah, which was formerly known as Gay Head, is the site of the Tribal Council for the Wampanoag Tribe of Aquinnah. Chappaquiddick Island is the ancestral home of the Chappaquiddick Wampanoag tribe, but the members of this tribe are no longer living on Chappaquiddick Island; many live across the water on the island of Martha’s Vineyard.

According to the 2010 census, there were 179 people living on the island with a racial makeup of 93.3% white, 1.7% African American, 0.6% Asian, and 0.6% Native American. 1This contrasts with the demographics of Aquinnah, which according to the same census had 344 people living in the town with a racial makeup of 53.49% white, 0.29% African American, 1.16% Latine, and 36.63% Native American. In order to better discuss the island of Martha’s Vineyard, it is imperative to understand its history in regards to the Wampanoag tribe.

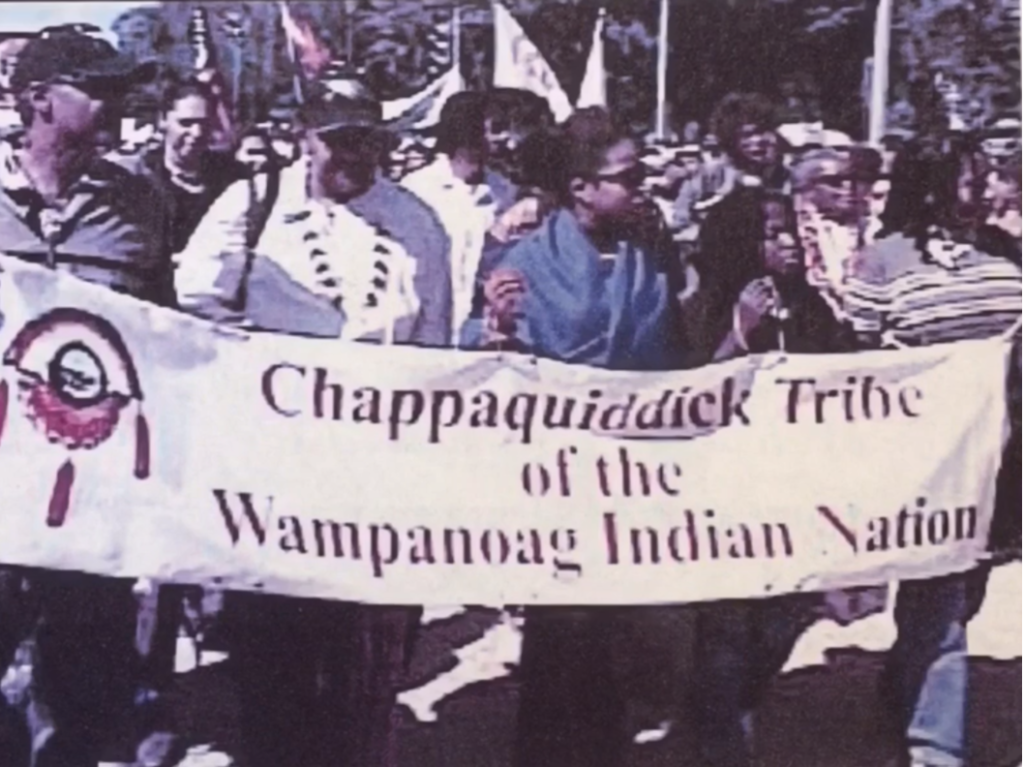

The ancestors of the Wampanoag people have lived for at least 10,000 years on the island of Noepe (Martha’s Vineyard), pursuing a traditional economy based on fishing and agriculture. 2 The Wampanoag Nation once included all of Southeastern Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island, made up of more than 67 distinct tribal communities, including the Wampanoag of Gay Head (Aquinnah). Today there are only six visible tribal communities; the Aquinnah and Mashpee Wampanoag are the only Wampanoag tribal communities who maintain physical and cultural presence on their ancestral homelands. The Aquinnah and Mashpee Wampanoag are also the only two federally recognized tribes in Massachusetts. 3 At the time of the first encounter between Europeans and the Wampanoag of the island in 1641, at least 3,000 Wampanoag people lived on the island. By 1645, two epidemics had killed almost half of the Wampanoag people on the island. 4 Today the Wampanoag tribe of Aquinnah counts 901 members, with around 300 living on the island of Martha’s Vineyard. While the members of the Aquinnah tribe of the Wampanoag are able to exert a physical presence on their ancestral home lands, the Chappaquiddick tribe of the Wampanoag are not able to do the same. The Chappaquiddick tribe had two reservations on Chappaquiddick island until the passage of the Massachusetts Indian Enfranchisement Act in 1869. 5 With the passing of the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869, the reservation lands were allotted to Chappaquiddick Wampanoag individuals and they were absorbed by the town of Edgartown. 6

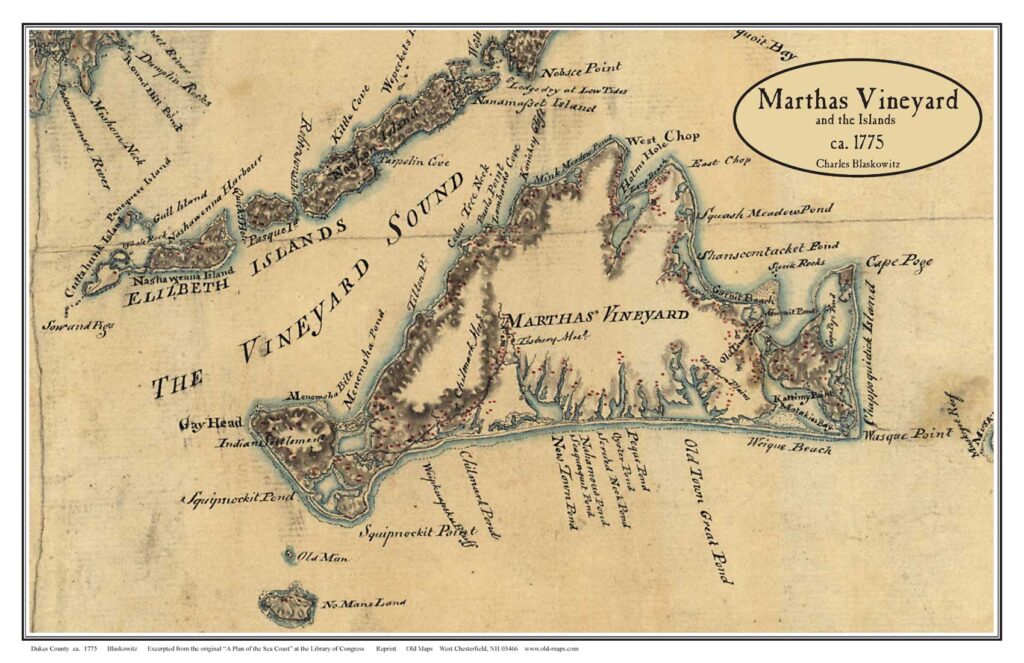

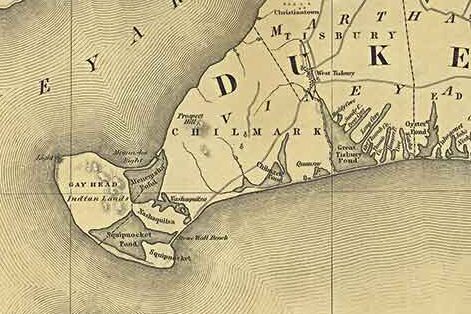

For both the Chappaquiddick and Aquinnah, the Massachusetts Enfranchisement Act of 1869 served to incorporate ancestral lands into the towns of Edgartown and Gay Head respectively. This can be seen in the above historical maps that demarcate the area of Gay Head as Indian Lands, until the passage of the act. The 1871 map of Martha’s Vineyard is the last historic map that acknowledges the presence of Indigenous people on the island. The Aquinnah Indigneous people played a large role in the town government of Gay Head from 1870 through the 1970s, making the alienation caused by the Act to be felt less strongly than the Chappaquiddick. In 1972 in response to the growing potentiality for encroachment on Tribal Common Lands, the Wampanoag Tribal Council of Gay Head, Inc. (WTCGH) was formed to promote self-determination among Wampanoag people, to ensure preservation and continuation of Wampanoag history and culture, to achieve Federal recognition for the Tribe, and to seek the return of Tribal lands to the Wampanoag people. 7 This council, along with the Chappaquiddick and four other Wampanoag tribes, filed a joint suit in order to regain land from the federal government. This suit affirmed the claim that Indian land had become federal land, meaning property could not be exchanged without federal consent. In 1987 the Tribal Council of Gay Head received federal recognition from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and received 485 acres of land. These 485 acres of land are represented on the digital map above by the purple polygons. The Aquinnah Tribe of Gay Head and the Mashpee were the only tribes who succeeded in gaining federal recognition.

“A coalition of six Wampanoag Tribes file suit against the Federal Government – in an effort to regain land …. the Chappaquiddicks, Christiantowners, Herring Ponders, Mashpees, Troys and Gay Headers. Robert C. Hahn, a lawyer for the Indians, said the suit maintained that sovereignty over Indian land was passed from the state to the Federal Government after 1789, meaning that the tribal property could not be surrendered or taken without Federal consent.” 8

New York times, December 19, 1981

Although the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head received federal recognition and some of their ancestral lands returned, the name of the place continued to be the colonial Gay Head until 1998. The name was officially changed back to the traditional Wampanoag name of Aquinnah in 1998, but the name of Gay Head colloquially lives on in the region. 9 This demonstrates the power of place names, and the difficulty in shifting settler colonial geography. The continued erasure of the Indigeneity of the Martha’s Vineyard landscape is underscored by the difficulty in changing the name back to its original Aquinnah.

The use of Indian-ness to describe the area of Aquinnah differs radically from the use of Indian-ness for Chappaquiddick Island. Aquinnah is used to assert the Indian-ness of the landscape and emphasize the continued importance of the Wampanoag tribe to the area. 10

This differs from Chappaquiddick, where members of the tribe are unable to inhabit their ancestral lands on the island, and live on the mainland of Martha’s Vineyard and the mainland of Massachusetts. 11 The use of the place name of Chappaquiddick appears to be more in the vein of justifying the continued colonial occupation by acknowledging the ‘former occupants’ of the land, which have vanished (in line with the myth of vanished native). Members of the Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe have continued to assert their identity and connection to their ancestral lands, even as they continue to lack federal recognition. However, federal recognition is merely one step in the path for greater Indigenous justice and land rights. That is to say, the recognition of Aquinnah land rights is just the first step.

In the interactive map, it appears as though official United States place names of Indigenous origin seem to be relegated to the periphery of the island. The center of the island is where the airport is located, and it seems as though the more built up areas are also along the periphery. There is also little overlap between the traditional Indigenous names and the U.S. place names using Indigenous words, highlighting the process of Inhabiting Indian-ness for justification of predominantly white settlement of land described by Barnd. 12 Another way to put it is the abundant use of Indigenous words to describe places (that are not the actual Indigenous names of these locations) represents white spaces inhabiting Indian-ness. One notes the spelling differences between the Indigenous spelling of “Tchepiaquidenet” and the settler spelling of “Chappaquiddick,” which is indicative of the way Indigenous forms of knowing are twisted to fit into the settler colonial project. The map is a visual accompaniment to this discussion of how the use of Indigenous place names can both reflect and contest the settler colonial landscape of the United States.

Footnotes

- Block Group 1, Census Tract 2003, Dukes County. United States Census Bureau

- “Wampanoag History.” Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head/Aquinnah. https://wampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/wampanoag-history#

- Kennedy,John H. “The Other Tribe.” Martha’s Vineyard Magazine, October 2017.

- Holm, Johan. “The Resurgence of Native American Identity: A Case Study of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah). LUP Student Papers, 2006.

- “Who We Are: Our History.” Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe. https://chappaquiddickwampanoag.org/our-history

- “Chappaquiddick.” Native Northeast Portal. http://nativenortheastportal.com/community/chappaquiddick

- “Wampanoag History.” Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head/Aquinnah. https://wampanoagtribe-nsn.gov/wampanoag-history#

- “Our History.” Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe. https://chappaquiddickwampanoag.org/our-history

- Holm, Johan. “The Resurgence of Native American Identity: A case study of the Wampanoag of Gay Head (Aquinnah).” LUP Student Papers, 2006.

- Barnd, Natchee Blu. Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, 2017.

- “Our History.” Chappaquiddick Wampanoag Tribe. https://chappaquiddickwampanoag.org/our-history

- Barnd, Natchee Blu. Native Space: Geographic Strategies to Unsettle Settler Colonialism. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University, 2006.